MoMA’s “Club 57” Review

One hosted their guests in an ‘opera house,’ the other in a basement of a Church.

One brought together Hollywood superstars, the other low key crew of art enthusiasts.

One was glamorous and cool, the other unpretentious and inclusive.

One welcomed Bianca Jagger on a white horse; the other threw a “Bongo Voodoo” party which ended with dead chickens being flung around and a raging bonfire in the middle of the club’s floor” as the New York Times describes it.

You’ve undoubtedly heard of Studio 54, not necessarily of Club 57.

Both of them captured a valid Zeitgeist of Reagan’s America.

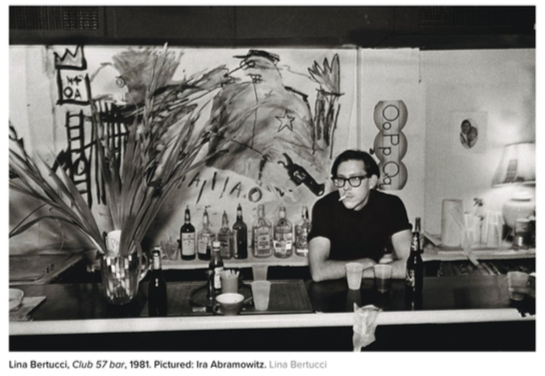

It’s after watching a series of “New Wave Vaudeville” set at Irving Plaza that Stanley Zbigniew Strychacki, invited Ann Magnuson to program the unhinge art calendar of the basement bar of the Polish Church on 57 st. Marks Place, in the then understanded East village. The rest became history.

“At any given time, the club was a dance hall, a screening room, a watering hole, a theater lab, an art gallery, or a self-styled ‘let it all hang out’ encounter group,” Ann Magnuson says in MoMA’s “Club 57” exhibition catalog. “Sometimes it was all those things at once.”

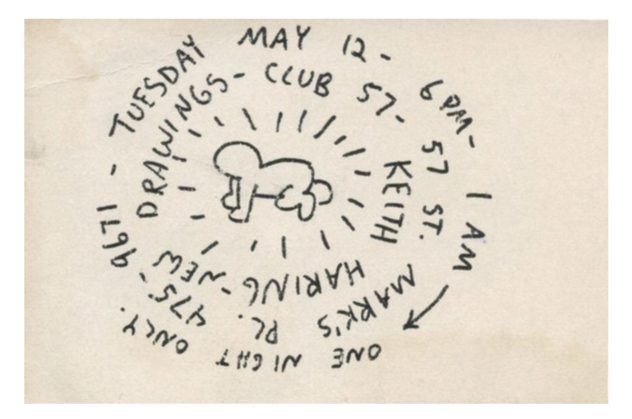

As we were strolling down the Titus galleries, in the bowel of the Moma, It seems like the club is still playing on the edge of the official art scene. There are pictures of Keith Haring’s Live performances, Richard Hamnleton famous ghostly ink blot figure, Mr. Scharf’s neon room as well as an endearing cacophony of videos and mix-and-match of hand designed and photocopied flyer. “Punk do-it Yourself aesthetic” as Magnuson puts it.

This exhibition reflects the act of creation. People were “encouraged to yell back at the screen, to interrupt it, to fool around during the screenings,” explains curator Ron Magliozzi. Plays were interactive, inclusive and really, what seems to be a considerable amount of fun.

Enthusiasms were cut short by the plague of the times: HIV and drugs. But also by a new form of creative sterilization: Gentrification.

“There was this mad rush to cash in,” Mr. Scharf explains in the New York Times. “It stopped being as fun as people became competitive with each other.”

What seems particularly relevant today is the debate over creation. The necessary link between art and institutional market, art and money, good taste and bad taste, ideas of political correctnesses and irreverence.

Unemployed Magazine believes in humor, believes in inter-disciplinary and that depth and erudition don’t have to be eyebrowed. And ultimately, in childish drawings of penises.

Club 57 is dead, Long live Club 57.

*the exhibition is on through April’s 1st 2018 at the Moma.